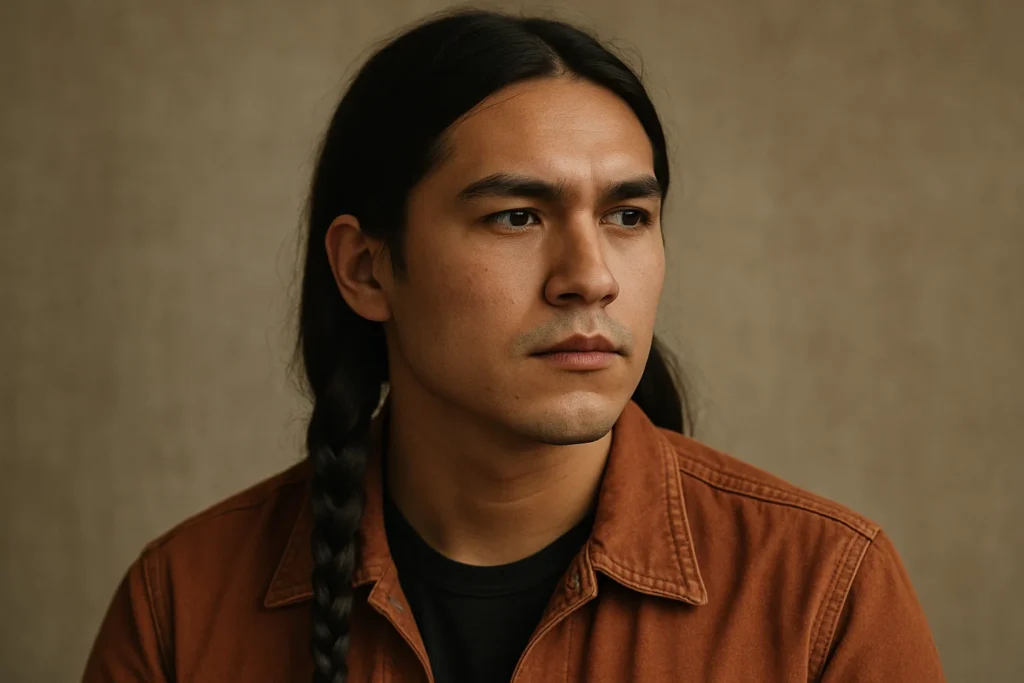

You probably remember the silence first. That’s what struck audiences back in 2015. Amidst the roaring bears, the screaming winds, and the grunts of Leonardo DiCaprio dragging his broken body through the snow, there was Hawk. Forrest Goodluck didn’t have the most lines in The Revenant, but he had the eyes. He held the screen with a quiet, burning intensity that made you forget he was a teenager who, just months prior, was sitting in a classroom in Albuquerque wondering if he’d ever catch a break.

It’s tempting to look at Goodluck’s trajectory—Oscar-nominated debut, Sundance accolades, gritty horror roles—and see a lucky streak. But the name is a misnomer. Nothing about his career has been accidental. He’s carved out a space for himself in an industry that notoriously struggles to figure out what to do with Native talent. He isn’t interested in being a token. He’s a filmmaker, a provocateur, and an actor who seems most comfortable when the material is uncomfortable.

Also Read: David Jonsson and Archie Madekwe

Key Takeaways

- The Big Break: Went from high school student to starring as Hawk in The Revenant (2015) alongside Leonardo DiCaprio.

- Tribal Roots: A citizen of the Three Affiliated Tribes, with ancestry including Diné, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Tsimshian.

- Behind the Camera: An aspiring director who started making short films in middle school, including a satire on eating endangered species.

- Genre Hopper: Seamlessly moves between prestige drama (The Revenant), indie hits (The Miseducation of Cameron Post), and horror (Blood Quantum, Pet Sematary: Bloodlines).

- Current Status: Recently seen in Lawmen: Bass Reeves and producing bold projects like How to Blow Up a Pipeline.

Who Was Forrest Goodluck Before the Red Carpets?

Albuquerque, New Mexico, isn’t exactly Hollywood, but for Forrest Goodluck, it was the perfect incubator. Born on August 6, 1998, he didn’t grow up with a silver spoon or industry connections. He grew up with stories. His background is a rich convergence of cultures: his father, Kevin, is Navajo (Diné), while his mother, Laurie, connects him to the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Tsimshian tribes from Alaska and the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation.

This multi-tribal identity shaped him, but so did his own weird, wonderful brain. He wasn’t the kid posing in front of the mirror practicing acceptance speeches. He was the kid behind the viewfinder.

His entry into the world of film is possibly the best anecdote to understand his personality. It happened in the seventh grade. The assignment? Make a commercial. Most twelve-year-olds would film their dog or a can of soda. Goodluck went dark. He directed a spot for a fictional company called “Rare Cuts.” The product was microwavable meals made from endangered species. It was satirical, biting, and a little bit twisted. That dry, intelligent humor has become his trademark off-screen, a sharp contrast to the often stoic characters he plays on-screen. He used his early acting paychecks not to buy cars, but to buy a Canon camera, teaching himself editing and framing before he was old enough to drive.

How Does a Teenager Just “Stumble” Into an Iñárritu Movie?

He didn’t stumble. He persisted.

The road to The Revenant was actually paved with rejection. Goodluck had been grinding away at auditions for years. He’d landed a role in a film called Man Called Buffalo, only to see the project fall apart. He was cast in Jane Got a Gun with Natalie Portman, but when the director Lynne Ramsay left the project, his character was cut from the script. He was getting close, tasting it, and then watching it evaporate.

So when the casting call for The Revenant came across his radar, he was skeptical. The breakdown called for a “Lakota boy.” Goodluck remembers reading it and rolling his eyes. “Ugh, okay, what is this going to be?” he thought. “You could have picked a more nuanced tribe.” He expected another leather-and-feather stereotype, a prop for a white savior story.

But he did his homework. He realized this wasn’t just a western; it was an Alejandro G. Iñárritu project. The role of Hawk wasn’t background dressing; he was the emotional fulcrum of the entire plot. Hugh Glass’s journey wasn’t about revenge for himself; it was revenge for his son.

The audition process was a marathon. It started with a self-tape from his living room in New Mexico. Then came the silence. Weeks of it. Finally, he and his mother were flown to Calgary. They didn’t go to a studio; they went to Iñárritu’s trailer in the middle of nowhere, two weeks before shooting started. The director, fresh off the success of Birdman, looked at the kid and told him, “Hawk is the heart and soul of this film.”

Goodluck got the part. He turned 16 on set.

What Was It Like Enduring the “Living Hell” of The Revenant Shoot?

You’ve read the headlines. The Revenant shoot was notorious. Sub-zero temperatures, remote locations, no green screens, only natural light. For seasoned pros like Tom Hardy and Domhnall Gleeson, it was a grueling test of endurance. For a kid whose biggest previous gig was a school play, it was a baptism by ice.

There were no luxury trailers waiting for him between takes. Instead, there was “boot camp.” Before a single frame was shot, the production team put Goodluck through the wringer. He had to learn to live like a 19th-century trapper. This meant learning to shoot flintlock rifles, skinning beavers, and starting fires with nothing but flint and steel.

The days were long and strange. Because they were shooting with natural light, they had a tiny window of time to actually film. Goodluck would spend hours in makeup, getting scars and dirt applied, and then sit in the freezing cold, waiting for the sun to hit the right angle. Then, chaos. “The light is here! Go, go, go!”

He wasn’t just acting alongside DiCaprio; he was learning from him. But he credits Tom Hardy with teaching him the mechanics of the job—how to hit a mark, how to work with the camera, how to keep your energy up when your toes are numb. It was a seven-month masterclass in filmmaking that no film school could ever replicate.

Why Was His Pivot to Indie Drama So Critical?

After a blockbuster debut, Hollywood usually tries to put you in a box. For Native actors, that box is often “historical epics only.” Goodluck smashed that box with a sledgehammer when he signed on for The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2018).

Gone were the furs and the rifles. In their place: a bad 90s haircut and a pair of gym shorts. He played Adam Red Eagle, a Lakota teenager sent to a gay conversion therapy camp. This role was pivotal because it allowed him to explore a specific, modern Indigenous identity: the concept of being “Two-Spirit.”

Goodluck didn’t coast on the script. He dove into research. He tracked down and met with a Winkte male—a Lakota term often associated with Two-Spirit identity—to understand what it meant to carry that spirit in the 1990s. He learned that the term had been twisted by colonization, turned into a slur on some reservations, and that playing Adam was a chance to reclaim the poetry of the identity.

In the film, Adam is sarcastic, grounded, and deeply skeptical of the camp’s religious dogma. He forms a trio of outcasts with Chloë Grace Moretz and Sasha Lane. Watching him, you see Goodluck’s natural charisma shine through. He’s funny. He’s dry. He proved he didn’t need a bear attack to be compelling; he just needed a good script.

Read more about the history of Two-Spirit identity here.

How Did Blood Quantum Flip the Script on Colonialism?

If you haven’t seen Blood Quantum (2019), you are missing one of the smartest horror movies of the last decade. The premise is genius in its simplicity: a zombie virus ravages the world, but Indigenous people are immune. The reservation, usually depicted in film as a place of poverty or despair, suddenly becomes the only fortress left.

Filming this movie took Goodluck back to the cold—this time in Quebec and New Brunswick. The conditions were arguably worse than The Revenant in moments. He recalls night shoots where the fake blood would freeze on the actors’ faces between takes. But the vibe was different.

On The Revenant, he was one of the few Native faces in a sea of white crew members. On Blood Quantum, he was surrounded by Indigenous talent. The director, Jeff Barnaby, was Mi’kmaq. The cast was a who’s who of Native actors, including Michael Greyeyes and Kiowa Gordon. Goodluck noted the irony in interviews: “Usually I’m the token Indian. Here, the white guys were the minorities on set.”

He played Joseph, a character caught between the safety of the reservation and his pregnant white girlfriend who isn’t immune. It’s a tense, gory, political thrill ride. Goodluck brought a desperate, frantic energy to the role, effectively shedding the “stoic warrior” trope once and for all. He was just a terrified kid trying to save his family in the apocalypse.

Why Is He Producing Films Now?

Most actors wait until they are 40 to start producing. Goodluck is already doing it. His credit as an executive producer on How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2022) signals a major shift in his career. He isn’t just waiting by the phone for an agent to call; he is helping to build the projects he wants to see.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline is a radical film. It’s a tense thriller about young environmental activists who decide to take drastic action. Goodluck plays Michael, a self-taught explosives expert who clashes with the group’s more pacifist members. The character is angry, intense, and deeply frustrated—a reflection of a generation that feels ignored by those in power.

By stepping into the producer role, Goodluck is putting his money where his mouth is. He’s spoken frequently about the need for “narrative sovereignty”—the idea that Indigenous people need to be the ones telling their own stories, not just acting in them. He understands that the real power in Hollywood lies in ownership.

What is Next for Forrest Goodluck?

He hasn’t abandoned the western genre entirely, but he’s updating it. His recent turn as Billy Crow in the Paramount+ series Lawmen: Bass Reeves sees him riding alongside David Oyelowo. But Billy isn’t a stereotype; he’s a young man with a love for dime-store novels and a flashy style, trying to figure out what justice looks like in a lawless land.

He also returned to the Stephen King universe in Pet Sematary: Bloodlines, playing Manny. It seems directors love casting him when things get dark and bloody. Maybe it’s that intensity he’s had since he was 15. Maybe it’s his ability to ground fantastical horror in real human emotion.

Forrest Goodluck is still in his twenties, yet his resume reads like that of a veteran character actor. He has survived the wilderness with DiCaprio, escaped a conversion camp, fought off zombies, and blown up oil pipelines (cinematically speaking). He is proof that the next generation of Native talent isn’t asking for permission to be stars. They are taking the center of the frame, looking the camera dead in the eye, and daring you to look away.

FAQs – Forrest Goodluck

What was Forrest Goodluck’s breakout role and how did it impact his career?

Forrest Goodluck’s breakout role was Hawk in The Revenant, which earned him critical acclaim and showcased his intense screen presence, helping to launch his career in Hollywood.

What is Forrest Goodluck’s cultural background?

Forrest Goodluck is a citizen of the Three Affiliated Tribes with ancestry including Navajo (Diné), Hidatsa, Mandan, and Tsimshian tribes.

How did Forrest Goodluck start his interest in filmmaking?

He started making short films in middle school, including a satirical commercial about endangered species, and taught himself editing and framing with his own camera.

How did Forrest Goodluck prepare for his role in The Revenant?

He did extensive homework on the character and the film’s themes, auditioned as a self-tape, and traveled to Calgary for a final audition with director Alejandro G. Iñárritu, who told him Hawk was the heart of the film.

What kind of roles is Forrest Goodluck known for, and what is he doing now in his career?

He is known for intense, gritty roles across genres including drama, horror, and indie films, and he is now also producing films to promote Indigenous stories and narrative sovereignty.